AWEN is the source of inspiration for poets writing in Welsh and is recorded as being of divine origin by poets going back to Taliesin. Writing about the 20th century Welsh-language poet Waldo Williams, fellow Welsh-language poet Euros Bowen asserted that, for Waldo Williams (in my translation) “awen is more than poetic inspiration; it is more than a divine influence on the poet. […..] It is itself a religion.”(*)

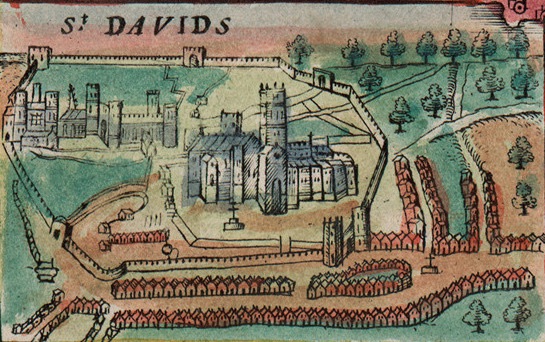

Although Waldo Williams was a Quaker, and widely thought of as a ‘Quaker poet’, this critic asserts that “ .. it would be a grave error to call him a non-conformist Christan poet” but one who worships in an “invisible and timeless place” (to quote one of his poems) beyond the confines of any temple. He further asserts that “the basis of his faith is not a trust in Christ, or a convincement about God. Its core is a metaphysical and religious convincement that God’s Awen gives life its meaning and purpose, and that awen enables ‘recognition’ (‘adnabod’ – a key term in his poetry) of the divine. After citing a number of references to awen in the poetry to make this case, Euros Bowen then examines the awdl (a long poem in traditional cynghanedd metres) ‘Tŷ Ddewi’ about the establishment of a centre of worship by St David in the place which now bears his name. He notes that, in spite of the Christian context of this foundation, Waldo Williams has St David replying to a passing Celtic pagan who tells him

“I will not serve

Christ hanging on a cross.

Give back the sun of the old shining world,

bring light to the land of the heart

without any pang of pain from an odious crown,

O, give us the birds of Rhiannon.” (**)

David replies that there is room for “the song of that queen” in the new religion alongside “the beauty of Brân the Blessed”. The response of the critic to this is that it sounds distinctly odd coming from a Christian saint, but is entirely consistent with the poet’s view of awen.

Here Rhiannon and her magical birds are the keynote to the old religion, the “shining world” evoked by the singing of the birds and which the modern poet seeks to incorporate into his view of the common bond between all religions and the convincement that there are many paths leading to one end encompassed by AWEN. She is recognised as a divine Queen, the literal meaning of of Rigantona, the Brythonic form of her name. Placing these words in a poem in the traditional metres of early Welsh poetry, imitating bards going back to Myrddin and Taliesin, traces her continuity from the old world to the new and brings her divinity back from the medieval tales in which her birds sing enchanting melodies from the Othwerworld and in which she features as an elusive figure on horseback, the mother of a wonder child, and one who disappears into the Otherworld to retrieve her child and is brought back by Manawydan, her divine lover.

So she lives among us still.

(*) In a review of Waldo Williams’ verse collection Dail Pren (1957) re-published in Cyfres y Meistri 2 : Waldo Williams ed. Robery Rhys (1981)

(**) These lines are from the translation of Dafydd Johnston in The Peacemakers , a volume of Waldo Williams’ poems in Welsh with facing English translations, mainly by Tony Conran (Gomer, 1997)